Amber Beilharz: What was your reason for founding Couplet Books, and what sets it apart?

Owen Davidson: Couplet Books is really the result of an aggregation of various previous commissioned poetry projects, such as We Eat Poets! (a series of fine food and poetry fusion events), and Give a Poem (a personal commissioned poetry service), among others.

The first of our publishing lines is the Poetry Companion Series, which will act as a celebration of different local areas, and a kind of alternative visitors guide. The aim is to build up a collectible series of books and pamphlets for various spots in London and the rest of the UK.

But where I think we differ from other poetry publishers is that, while we are producing titles which are designed to be commercially successful in their own right (which is not unique, but neither is it the norm), we are also working with businesses to develop poetry projects relevant to their needs and the experiences of their customers.

All of the founders of Couplet Books, Jon Stone, Kirsten Irving and I, believe that, in spite of its popularity, poetry is still seen as a marginal activity. That is what we want to challenge, and the way we will try to do it is to show that we can use poetry to respond to the world around us and produce work which is both striking and accessible. At Couplet Books, we think that there are lots of ways to make poetry more accessible, and that there should be more consumable poetry.

At the same time we are acutely aware that to achieve this, it is important to ensure that quality is at the forefront of what we do. To that end, we concentrate a lot of effort on selecting the right poets, and ensuring that they are really engaged with the commissioned work we ask them to undertake. With the HAMPSTEAD POETRY COMPANION, the first in that series, we are asking three poets to write four poems each about different places in the locality, and all of them have demonstrated strong associations with the subject matter of their commissions.

I sometimes paraphrase Steve Jobs when I am explaining what we are trying to do, by saying that often people don’t know what they like until you show it to them. That is the aspiration of Couplet Books, to present people with a poetic perspective on the things around them. People’s eyes light up when we say that we are sending a bunch of poets to various spots in their area to find inspiration there, and write poems about them, and the resulting material is very well received. It’s a popular thing, and that is as it should be.

AB: Can you tell us more about the Daily Couplet? Why the focus on couplets?

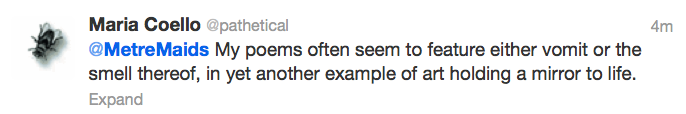

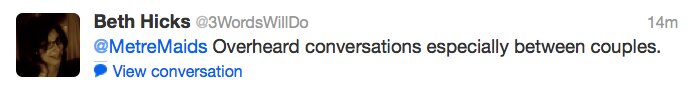

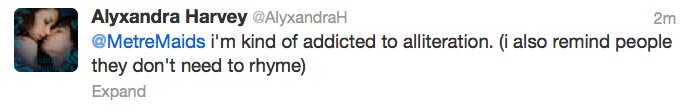

OD: Every day we publish a different couplet on our website, on our Facebook page, and on Twitter.

Our motivation for this is really two-fold (no pun intended!). For the first part, we wanted to create something fun for poets to interact with, and this was a very simple idea which ties in with our name. We are developing some other interactive, playful features at the moment, and they will hopefully begin to appear on the site in the next couple of months.

The other consideration was to provide a platform for poets so that they can reach a wider audience. The idea is that if there is a particularly catchy, clever, quirky, or interesting couplet somewhere in a poet’s back catalogue, or if they want to write something new, they can submit it, and hopefully some people who aren’t aware of them can read it, and investigate a little further if they like what they see.

From next week we will start to publish the submissions we have been stockpiling.

-

- Couplet Books, forthcoming.

AB: What is responsive poetry? What does it mean to you?

OD: Responsive poetry, as far as we are concerned, is poetry which responds to a certain place, thing, or idea. In the case of the Poetry Companion Series, this means writing poems that respond to particular places in a specific area; such as the local cinema, coffee-shop, or park; or the ‘idea’ of the place as interpreted by local poets.

For our forthcoming HAMPSTEAD COMPANION, we are commissioning 12 poems about specific places we think ought to be included, and we have an open submissions process for anyone who has something to say about the area. Here it is on the map. The deadline for entries is the 27th of April, and so far we have been impressed with the range and quality of responses which have come in. Clearly, people have a lot of affection for the places in which they live.

In a wider, and, I suppose, more pragmatic context, responsive poetry is a concept we are trying to explore with various businesses as a way to reimagine their brands. We have on the horizon a couple of residencies whereby poets will be tasked with responding to a specific brief which aims to put in to words, or rather, to put in to poetry, the experiences people have when they interact with a place. Hopefully this will stimulate a bit of engagement with the customers of that business, and again provide a platform for the poets involved, and poetry in general.

AB: What catches your eye in the submission pile? Is there anything specific you’re currently looking for?

OD: As we are based in London, we are very fortunate to be surrounded by a great deal of exciting poets, and poetry organisations. Consequently, retaining a consistent focus on what we are doing is tough, because there are so many interesting projects going on. That said, we are always attracted by those poets who are willing to be playful, keen to try new things, and comfortable writing to commission. Two initiatives which recently came to my attention, and perhaps exemplify what I mean, are Poetry Digest, run by Chrissy Williams and Swithum Cooper, which is an edible magazine – a previous edition featured a number of guest poets printing short edible poems on to cupcakes; and Penning Perfumes, run by Claire Trevien, whereby poets are asked to smell a perfume, and use the ensuing sensual experience as the starting point for a poem. Fuselit, run by our own Jon Stone and Kirsten Irving, is another hotbed of interesting projects.

AB: What else are you working on at the moment? Any secret projects you can clue us in on?

OD: Some of our previous endeavours are undergoing a refurb, and will be informing various projects soon. One example being the We Eat Poets! series of events we ran in London last year.

Something very similar will be rolled out again later this year, with each event timed to coincide with the launch of a different Poetry Companion.

The premise behind this series of events was born out of the feeling a few of us had that while it is (in London, at any rate) pretty easy to find good poets standing up and reading or performing good poetry, it is really hard to find a reading which is a good event in itself.

So we got together with a fine foods company and a really quirky restaurant in central London, and put on a 4-course meal loosely related to a specific theme. Then we asked 3 poets to respond to the theme, the menu and the venue, and come along to the event to sit incognito on the tables with the other paying customers. As people entered, they were serenaded by Spanish guitar, and when everyone was seated, enjoying their first course, the first poet stood up unannounced (much to the amazement of the other diners on his table), and began his set. Each break between courses was punctuated by a different poet, culminating, at the end of the event, with the performance of a poem written on the night, incorporating specific details particular to the happenings that evening, and including words suggested by the audience at various points throughout proceedings.

More of those will be happening in London soon, and hopefully further afield a little later on.

AB: What was the first poem you ever fell in love with?

OD: I think ‘love’ would be going a bit far, but the first poem I remember, is “Cargoes” by John Masefield. I was either 7 or 8, and our teacher sprung this on us and made us all memorise it.

Looking back, I think what captivated me was that it was the first time I really got an inkling that there were layers to this thing which seemed at first sight to be so insubstantial; the words somehow had more to them than usual, the sounds were evocative, and I noticed a rhythm to it. I don’t think these were new feelings, per se, just that it was the first time I noticed being affected by them all at once, and in response to something so short and simple.

Random House, 2004.

AB: What’re you reading now? What do you think we should be reading?

OD: At the moment I am reading 52 WAYS OF LOOKING AT A POEM by Ruth Padel, which is thoroughly excellent, and is highly recommended to anyone, poet or not. I think it is incredibly important to question how you interpret things (not just poems), and in this book it is done in a very intelligent, accessible way. On the poetry side, I am sifting through lots of work by people who have submitted couplets for the Daily Couplet to try to get a better understanding of who we will be featuring.

AB: What aspect of the outside world inspires you the most?

OD: A large portion of my time is given to thinking about how we can use poetry to reimagine things around us, and I am constantly both amazed and daunted by the range of possibilities out there; it is true that we live in a world not of poetry, but of poetries.

I was chatting recently with a poet about taking decisions on what to write about, and how often the problem is not really finding the ‘what’, but rather understanding the ‘why’. The key for us is tp match the interests of the poets to the commissions – we are working with an artisan butcher shop right now, and will be sending a poet to one of their tastings in the next couple of weeks; we happen to know a poet who is absolutely crazy about this sort of thing, so that one was very easy to reconcile. When we get it right, the poet’s imagination can really run wild, and the result is generally some really authentic material which is well received by the audience. This is the premise on which most of our work is based, and it is what really inspires me to keep doing what we do.

AB: Why poetry?

OD: I am not all that well informed about the contemporary situation in the US, but in Britain, poetry seems to occupy a dichotomous place in the public consiousness. On the one hand, the poetry scene is thriving; it is fabulously rich and exciting, with all sorts of talented people producing amazing work; poets popping up at festivals and teaching in schools all over the place; and lots of coverage on radio and in newspapers. Yet in spite of this apparent popularity, poetry is still seen as a marginal activity, and that is what we are keen to address through the things that we publish. I guess that is what keeps me involved, and retains my interest.

Owen Davidson.

Owen Davidson grew up in the North East of Scotland, before spending much of his early adult life working, travelling, and studying in France, Spain, Germany, Russia, and the USA. For the last 5 years has been living in London, working on a number of different commissioned poetry projects, such as We Eat Poets!, the critically acclaimed series of fine food and poetry fusion events. In 2012 he founded Couplet Books, a poetry publisher specialising in responsive poetry. Its first project is the Poetry Companion Series, a range of pamphlets and books which act both as celebrations of local areas, and alternative visitors guides.